Travel: From Tucson, drive north on Oracle Road, AZ-77. Pass Ina Road and turn right on Magee Road. Go 1.5 miles to the Iris O. Dewhirst Pima Canyon Trailhead. Or, from Ina Road take Christie Drive north for 1.4 miles and turn right on Magee. The generous, paved lot is on the right. There is a drinking faucet but no other facilities.

Distance and Elevation Gain: 9.6 miles; 3,320 feet of climbing

Total Time: 8:00 to 11:00

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation challenging; low Class 5; serious exposure; Carry all the water you will need and hike on a cool day.

Maps: Tucson North; Oro Valley, AZ 7.5' Quads; or, Pusch Ridge Wilderness, Coronado National Forest, USDA Forest Service, 1:24,000

Date Hiked: December 3, 2019

Pusch Ridge Wilderness Bighorn Sheep Closure: It is prohibited to travel more than 400 feet off designated Forest Service trails from January 1 through April 30, bighorn sheep lambing season. Table Tooth is off-limits during that time period. No dogs, ever.

Quote: I have been traveling the southwestern wilderness, coming out to places that open my life like a knife slipping the seam of an envelope. Craig Childs

Table Tooth appears as Table Mountain's companion spire from Oro Valley. On the approach it looks like a barrier wall. From the razorback summit ridge you see it for what it is, a lengthy granitic blade. (Thomas Holt Ward, photo)

This image of Table Tooth shot from "The Molar" is representative of the true challenge and risk. (THW, photo)

Route: My partner climbed with a friend in 2018 with little route information. They experimented with several approaches and consumed 11.5 hours. On this climb we honed an expeditious route and it took 8:45, including plenty of top time. Hike northeast on the Pima Canyon Trail. Leave the trail at 4,380 feet and pitch up a north tributary and then a series of slopes to the east ridge. Scramble west to the summit.

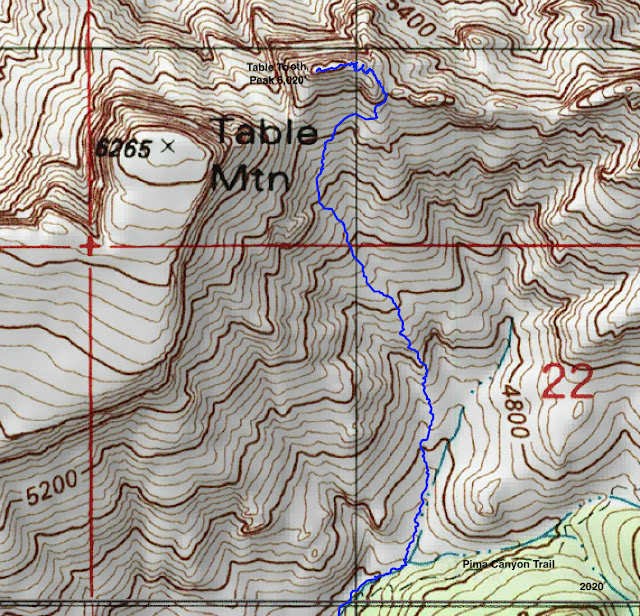

This is a detail map of our off-trail route north of the Pima Canyon Trail.

Pima Canyon Trail

From the trailhead, elevation 2,920 feet, make quick progress up the exquisitely beautiful Pima Canyon Trail. A lovely cristate saguaro lives above the path at 0.5 mile. It is often overlooked. For elaboration on this segment of the hike, please refer to Pima Canyon to Finger Rock Canyon via Mount Kimball. Below, The Cleaver exhibits ceaseless appeal at 1.5 miles.

The cascading call of a canyon wren was an auspicious sign. At 3.0 miles, the footpath crosses a sheet of Catalina Gneiss with a series of bedrock mortar holes used for grinding corn.

A few steps further on, walk onto a slab to locate a dam constructed in the 1960s by Arizona Game and Fish. It was intended as a water source for bighorn sheep and other wildlife. Below, the dam is image-left. The east escarpment of Table Mountain is image-center, and Peak 5,985' and the Wolf's Teeth are on the right.

To East Ridge of Table Tooth

At 3.7 miles, the trail descends to the Pima Canyon wash, crosses it, and climbs above the canyon floor. Leave the trail at the streamway, elevation 4,380 feet, shown. The summit is only 1.1 miles afar but allow three to five hours roundtrip. Boulders are big and slick, and there's a mix of canyon clutter and swaths of gneiss. In less than 0.1 mile the canyon splits; stay in the main canyon on the right.

In 0.2 mile, leave Pima Canyon and bear left into a north tributary. Looking at the photo below, the route goes into the side canyon left of the outcrop, image-center.

This secondary draw sheds water from the saddle between Table Mountain and Table Tooth. The drainage splits again shortly. Imagine where the saddle would be and aim for it. (THW, photo)

This image was shot from the drainageway. Table Tooth is on the skyline at the left. The goal of this segment is to hit the east ridge at the saddle to the right of the summit. The terrain is riddled with cliff bands so navigation is critical. This route avoids all impediments.

At approximately 4,740 feet, watch carefully for a stacked black boulder with a white vein, shown here on the right above my partner. Leave the dry wash and climb to the right of the boulder cluster.

Pass the next much larger outcrop on its left.

This photo looks back on the second outcrop. Climbers were beginning the grassy slope section. The magnificent stone bastion across Pima Canyon is Prominent Point West, one of the most monumental hikes in the Pusch Ridge Wilderness. (THW, photo)

As Pusch Ridge slopes go this one is amazingly accommodating. It is free of obstacles and steep but never too steep. (If you cliff out look around for another route.) Resurrection plant makes stepping platforms and the ground sparkles with mica and quartz crystals. In 2018, my partner climbed to the Table Mountain saddle, image-center, and made an unsuccessful attempt from there before coming around to the east ridge.

This time we avoided the saddle and headed directly for the east ridge. At 5,400 feet, bear due north and aim for a break in a north-south ridgelet. Hit it to the right of the rock wedge, image-center at skyline.

If you are on track and lucky you will pass by this miner's hoe at 5,520 feet. Please leave this historical marker in its place for future climbers to enjoy.

At about 5,700 feet, gain the ridgelet; it is on par with the Table Mountain saddle. Below, Table Mountain is on the left and the south wall of the Tooth is on the right.

Climb another 100 feet to reach the east ridge. The saddle is just beyond this tree.

Arrive on the summit ridge west of this outcrop at 4.6 miles, 5,820 feet. The crest is 0.2 mile west. The vertical cliffs, nearby pinnacles, and the knife edge that awaits are composed of Wilderness Suite Granite and Gneiss. The rock is characterized by widely spaced vertical joints. Fractures serve as channels for weathering and erosion. Rock shattered, ravines were cut, and the vertical formations found on the southern end of Pusch Ridge were created. Way back in geologic time Table Mountain and Table Tooth were one rock. ("A Guide to the Geology of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: The geology and life zones of a Madrean Sky Island." Arizona Geological Survey, Down-to-Earth, #22, by John V. Bezy, 2016.)

East Ridge to Summit

The east ridge at the saddle presents as a shaft of slanted rocks. Work west along the north side of the backbone, right where the stone wall meets the dirt. We saw faint signs of use.

In 0.1 mile, the passage ends where walls to the north and south pinch at an apex with a tree, image-left. The crux is the wall on the north side.

Exposure from here to the summit is significant so be steady and methodical. Go behind the tree and then make one Z turn up the lower wall: right, left, right. The ledges vary from a few inches to a foot wide. The last turn puts you on a flat ledge about four feet long and about 12 inches wide to start, then tapering.

The Class 5 move launches from this narrow landing. A bulge in the eight foot pitch makes it more difficult. Skilled climbers only! In 2018, my partner free climbed the pitch and then placed (and left)

webbing with overhand loops tied around a tree at the top. We used the old webbing going up but placed

new webbing in 2020 for our descent and left it there.

The next two images are a pretty good indication of the exposure and difficulty. My friend on the wall has nearly completed climbing all 689 peaks over 13,000 feet in Colorado.

She was more comfortable free climbing than relying on two-year-old webbing.

We heard that other climbers discovered a go-around for the crux. We explored but did not find a pitch we were comfortable with. It is quite possible that they are simply better climbers (than me, at least). I found the downclimb easier. I rolled onto my belly, found a couple of solid holds in the rock and then used the webbing to drop the last six inches to the ledge.

Once you are at the top of the crux there are two choices. The more difficult is a Class 4 pitch up the immediate wall. We walked a couple of steps around the corner to the east and did a more protected scramble up onto the spine, shown.

The reef is seriously airy but the rock is beautiful--clean, solid slabs. The ridge presents itself in sections. There are limited choices. Pick a course that is most comfortable for you. The scariest move for me was going on the left side of the boulder my partner is approaching.

This photo shot on the return illustrates that place well. My friend is about to turn and face the rock. I shuffled along with my hands hooked over the boulder. My feet were on a slant and the ground just fell off into space. The north side of the ridge is even more vertical and the drop is deeper.

Raw desire built up over the years and just enough courage propelled me onward. I reveled in this climb but I won't be testing my fate with a repeat. Often I contemplate with gratitude the goodwill of a mountain that allows me safe passage. (THW, photo)

This shot of the "Staircase" was taken on our return. Go around the boulder at the top of the stairs on its right side and arrive on the small but comfortable summit spire. (THW, photo)

This image looks back from the top boulder. It highlights the ridge segment below the staircase.

Table Mountain completely mesmerizes climbers on the Tooth. The two are so close you could have a casual conversation with someone standing on the parent mountain. The peak register was placed in 1977. One or two parties have signed in most years since.

Look northeast to conoidal Samaniego Peak, the Mount Lemmon dome, and mythical Cathedral Rock. (THW, photo)

Creamcups provide a lively and sweet contrast with all that granite. They are in the poppy family and grow along canyon bottoms. (THW, photo)

No comments:

Post a Comment