Essence: The sheer force of Big Hatchet Peak cleaves the horizon, beckoning desert wanderers traveling throughout southwestern New Mexico. The state's eighth most prominent peak is located in the remote Bootheel, a borderland block protruding into Chihuahua, Mexico. The journey begins with a rugged drive through the fierce beauty of the Chihuahuan Desert. The track rises from creosote bush bottomland onto a mesquite bosque bajada and on up into a piñon-juniper woodland. A strong social trail takes the hiker to the dip slope of the master mountain. From there, the ascent is gradual and accommodating through limestone boulders sheltering symmetrical agave. From the highpoint of the range, the full-circle vantage point encompasses sky islands of southeastern Arizona, the Sierra Alta range in Chihuahua, and the imponderable Sierra Madre Occidental in Sonora, Mexico. The Continental Divide Trail parallels the Big Hatchet Mountains on the northeast. This will likely be a hike of solitude, though thru-hikers occasionally sign the summit log. The hike is within the Big Hatchet Mountains Wilderness Study Area administered by the Bureau of Land Management.

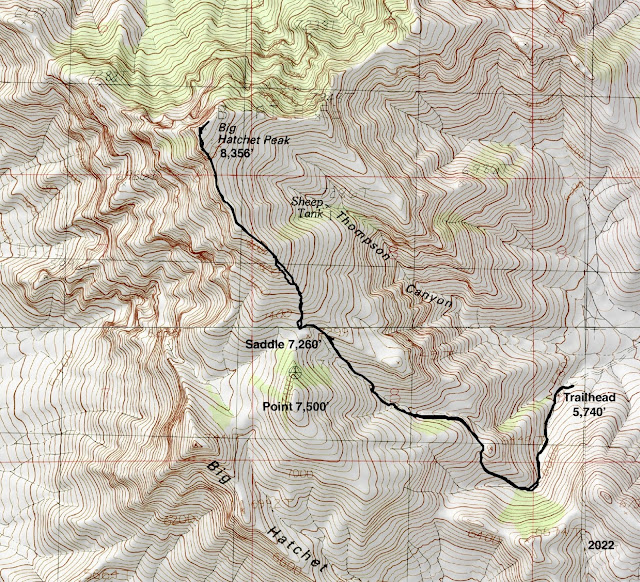

Travel: A 4WD vehicle with high clearance is required to reach the trailhead. We followed a friend who had perfected the route. Three highways intersect in Hachita: NM-146 comes south from Exit 49 on I-10. NM-9 runs east-west through town. NM-81 begins in Hachita and goes south to the Port of Entry at Antelope Wells. The Hachita Food Mart and gas station (call ahead to confirm) is a happening place. Measure distance from the intersection of NM-9 and NM-81 and go south on NM-81 toward Antelope Wells. Big Hatchet is straight ahead while driving through the Hachita Valley. At 10.4 miles (between Mile Marker 34 and 33), turn left on Hatchet Road, CR 95. It's dirt from here on. At 11.0 miles, take the right fork. Turn right at 13.1 miles on Commodore Road. There are a maze of roads; stay on the main track, one lane with washboard. At 16.2 miles, four roads intersect. Go left, following the sign for Public Land Access. Enter the Wilderness Study Area. It might feel like you are going too far east. Stay on route. At 21.4 miles, the road splits. Take the right branch (straight ahead) and start up Thompson Canyon. Pass a square, stone water tank filled with water. The road degenerates, becoming rocky and narrow. Cross the Continental Divide Trail at 22.4 miles. As the track climbs the alluvial fan, mesquite will scrape your vehicle. Consider parking in a turn-around lot at 23.7 miles. Clearance issues become strained from there. The road dips in and out of radically pitched narrow ravines. Excellent approach and departure angles are required. Park at the end of the road, mile 25. Allow 1:15 from Hachita. Note: the road through Thompson Canyon is prone to washout and you may have to park some distance from the trailhead. Distance and Elevation Gain: 5.4 miles; 2,650 feet of climbing

Total Time: 4:30 to 6:00

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 2; no exposure (precipice can be avoided)

Maps: Hatchet Ranch, Sheridan Canyon, U Bar Ridge, Big Hatchet Peak; New Mexico 7.5' USGS Quads

Date Hiked: January 31, 2022

Quote: We tend to think of landscapes as affecting us most strongly when we are in them or on them, when they offer us the primary sensations of touch and sight. But there are also the landscapes we bear with us in absentia, those places that live on in memory long after they have withdrawn in actuality, and such places--retreated to most often when we are most remote from them--are among the most important landscapes we possess. Robert Macfarlane

Total Time: 4:30 to 6:00

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 2; no exposure (precipice can be avoided)

Maps: Hatchet Ranch, Sheridan Canyon, U Bar Ridge, Big Hatchet Peak; New Mexico 7.5' USGS Quads

Date Hiked: January 31, 2022

Quote: We tend to think of landscapes as affecting us most strongly when we are in them or on them, when they offer us the primary sensations of touch and sight. But there are also the landscapes we bear with us in absentia, those places that live on in memory long after they have withdrawn in actuality, and such places--retreated to most often when we are most remote from them--are among the most important landscapes we possess. Robert Macfarlane

The block-faulted Paleozoic limestone cliffs of Big Hatchet Peak upthrust four thousand feet above the Playas Valley. The Omnidirectional Relief and Steepness system for measuring mountains ranks Big Hatchet number one in New Mexico. (Thomas Holt Ward, photo)

Route: From the trailhead ascend south on a footpath along a tributary of Thompson Canyon. The route swings northwest. Upon reaching the saddle between Point 7,500' and Big Hatchet Peak, climb the south ridge off-trail to the summit.

Hachita was a vibrant mining town in the late 1800s. Currently, the dilapidated village has about 50 residents. A stone mason's mastery withstands the ravages of time at St. Catherine of Siena Catholic Mission Church. According to the shop keeper at the convenience store, the diocese stripped the statuary from the building in the early 2000s and has no intention of revitalizing the beautiful sanctuary. (THW, photo)

The climber's blade, the south ridge of Big Hatchet Peak, is visible from Hachita. Zeller Peak, 7,426', is the domed subsidiary summit west of the highpoint.

Judging from trip reports, the trail was faint and fragmentary for decades. In 2022, while it was slightly overgrown and showed little sign of use, the boot-worn treadway was dependable and an indispensable assist navigating to the saddle. Two forks of Thompson Canyon, from the south and southwest, converge in the vicinity of the unsigned Big Hatchet Peak trailhead, elevation 5,740 feet. The route goes up the south fork, image-left. The trail leaves from the west end of the parking area, immediately drops into the ravine and pitches up the other side.

It crosses the dry arroyo at 0.1 mile and then recrosses several times.

Limestone cliffs of the Paleozoic Era (541-252 million years ago) surround and embrace the hiker. You will be in the company of this square-block peninsula for most of the hike.

The Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion is the largest in North America covering nearly 250,000 square miles; most of it lies south of the U.S.-Mexico border. It is considered the most diverse desert in the Western Hemisphere. Within the canyon and on north-facing slopes are elder piñon-juniper stands and sandpaper oak. Ubiquitous mountain mahogany is coupled with evergreen sumac, silktassel, and glistening beargrass. The fruits of cane cholla are eaten by desert bighorn sheep which are known to roam in the Big Hatchet Mountains.

At 0.5 mile, the route leaves the drainage, curves to the northwest and ascends toward Point 6,449' on a crushed rock treadway. In the adjacent drainage the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish has installed an elaborate system for supplying water to wildlife. The tanks are visible from the trail.

Pass a magnificent limestone breccia boulder. Breccia is composed of pebble and boulder-sized clasts cemented together by a fine-grained matrix. The angular nature of these clasts indicate they have not been transported very far from their source. Our geologist companion surmised we were in the fault zone.

At 0.8 mile, pass over a small ridge west of Point 6,449'. The trailhead and our vehicles are pictured in the center of this image. The trail rounds the corner and ascends the upper reaches of the southwest fork of Thompson Canyon.

The trail crosses the ravine at 1.3 miles and climbs aggressively up the draw between Point 7,500' and the peninsula. On the return, this stretch was toe-jamming steep. (THW, photo)

Gain the broad south ridge of Big Hatchet at 7,320 feet, 1.7 miles. This cairned juncture is above the 7,260-foot saddle and slightly north of the insignificant rise, Point 7,299'. The route up the south ridge is off-trail from here to the summit.

The way is clear and there are no obstacles. We found crinoid fossils embedded in limestone boulders.

Cabbage head agave (a. parrasana) are abundant on the ridge. Native to Mexico, they favor limestone soils.

Within a half mile of the top, the dip slope narrows. Typical of a tilted fault-block, Big Hatchet has a phenomenal crashing drop to the west. You can moderate how close you come to the precipitous escarpment. It's easy to fall in love with this "hostile" landscape while walking along the thrilling, airy cliffline.

Arrive on the roomy summit at 2.7 miles. While we found reference marker No. 2 placed in 1938, the Big Hatchet benchmark was missing from its post. (THW, photo)

There is a solar powered weather station on the summit and an entertaining peak register. The most noble entry was posted by a hiker who was lamenting his last day on the Continental Divide Trail. Earlier the same year, he hiked the entire Appalachian Trail. Wow. The field of vision is commanding if not other-worldly. Look south into the swallowing distances of Sonora and the Sierra Madre Occidental, "Western Mother Mountain Range." (THW, photo)

To the west is the Playas Valley and Peloncillo Mountains of New Mexico, and the snow-capped Chiricahua and Pinaleño mountains in Arizona.

At 8,565 feet, Animas Peak is the highpoint in Hidalgo County, New Mexico. The Animas Mountains sky island is privately owned by the Animas Foundation and is off-limits to hikers.

The Alamo Hueco Mountains are but a breath away from the international border. South of the range is the state of Chihuahua.

Walk along the free-fall, overhung north face to sense the empty space surrounding this mountain on three sides and for a captivating view of Zeller Peak.

Descending the south ridge, I paused to consider the wonders Earth creates by moving large crustal blocks.

Looking at the image below, the squared off peninsula is on the left, Point 7,500' and the saddle are on the right, and the descent draw is image-center. The tempting peninsula drew one in our group off course. When you get to the saddle area, watch for the cairn marking the trail into the draw at 3.7 miles. In 2022, there was no snow in January, not even in the north slope woodlands.

It is a long haul from anywhere to Big Hatchet Peak. Remote has its advantages. This is a windshield shot of the setting orb finding an opening (briefly!) in a brooding sky to set grasses blazing along AZ-338.