Travel: From US 60 east of Apache Junction, turn north on Peralta Road. In one mile the road turns to well-graded dirt suitable for all vehicles. You are already in the big desert with chainfruit cholla, palo verde, pricklypear and saguaro abutting the road. Bluff Spring Mountain is visible on the drive to the right of Weavers Needle. Pass Carney Spring Trailhead at 6.1 miles and go over a cattle guard and into Tonto National Forest at 7.0 miles. Park at 7.2 miles in a large lot. This is a popular trailhead in the Superstitions. Almost five million people think of this wilderness as their backyard so get there early, especially on weekends. Pit toilet, no water, no fees.

Distance and Elevation Gain: 10.5 miles for the out-and-back with 2,600 feet of climbing. The west ridge descent shaves 0.4 mile but will take about as long.

Total Time: 6:00 to 8:00

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 2+ with mild exposure; wear long pants; take all the water you will need and hike on a cool day.

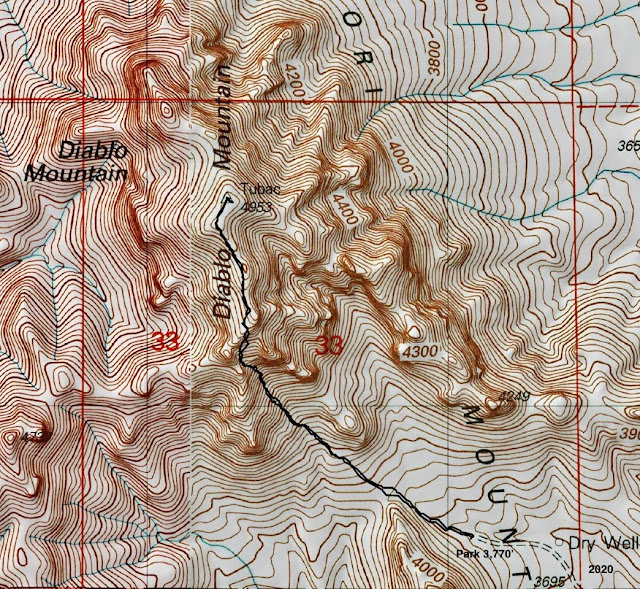

Maps: Weavers Needle, AZ 7.5' USGS Quad; or Superstition Wilderness, Tonto National Forest, US Department of Agriculture

Reference: Hiker's Guide to the Superstition Wilderness, by Jack Carlson and Elizabeth Stewart. Tempe, Arizona: Clear Creek Publishing, 2002

Date Hiked: January 30, 2020

Quote: So there I lie on the plateau, under me the central core of fire from which was thrust this grumbling grinding mass of plutonic rock, over me blue air, and between the fire of the rock and the fire of the sun, scree, soil and water, moss, grass, flower and tree, insect, bird and beast, wind, rain and snow—the total mountain. Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

Water sloshes over bedrock in Barks Canyon below Bluff Spring Mountain at the junction of the Bluff Spring and Terrapin Trails. (Thomas Holt Ward, photo)

Route: Hike north on the Bluff Spring Trail (BST). At the junction with the Terrapin Trail, stay on the BST as it swings east into Bluff Spring Canyon. Just before the junction with the Dutchman Trail, climb northwest on a cairned route to Point 4,041'. Hike west to the summit. Either return as you came or descend west off-trail to the Terrapin Trail. Walk south to rejoin the BST.

Bluff Spring Trail to Start of the Climb

Sign the trail register at the northeast corner of the parking lot, elevation 2,420 feet, and enter the Superstition Wilderness. (THW, photo)

The Peralta Trailhead is located at the base of the Dacite Cliffs. The view from the parking lot is startling and unparalleled. Dacite, andesite, rhyolite, tuff and breccia are the common igneous rocks found in the Superstition Wilderness deposited approximately 25 million years ago by volcanism. (THW, photo)

The trailhead serves three major trail systems: Peralta Canyon, Dutchman, and Bluff Spring. The Dutchman Trail and BST share treadway momentarily while crossing the Peralta Canyon watercourse.

Then, take the left fork onto the BST. The Dutchman Trail also goes to Bluff Spring but the BST is faster and shorter. The broad trail is highly engineered with log and stone steps. Big steps. After January rains the exceptionally green flora contrasted with the chocolate-colored minarets across Peralta Canyon. (THW, photo)

Top a low ridge above Barkley Basin at 0.3 mile. The Dutchman Trail is running along in front of the low hills.

(THW, photo)

The path turns north and roughly follows the ridge. It steps up a stone ramp and then weaves through lumpy, blond dacite. I was surprised to see evidence of equestrian use on the rough trail.

This wondrous hike is all about diversity of shapes. Agave have flared spikes, pricklypear have platters, chainfruit have strings of round buttons, and the saguaro are pillars. The standing rocks are even wilder. Some are spheroidal, others balanced. There are effigies, lines of post piles, blades, horns, wings, stacks, and spires. (THW, photo)

Bluff Spring Mountain is visible for the first time at 0.9 mile as the trail swings west and contours past a northwest fork of Barks Canyon. Weavers Needle comes into view at 1.25 miles on a small saddle. Give up 130 feet to the floor of Barks Canyon.

Water is present occasionally in Barks Canyon below Point 3,179'. Carlson and Stewart write, "Almost everyone gets lost around here where the trail goes up the bed of the wash." We were off the trail for a short time outgoing but coming back had no trouble staying on track.

The longstones of Barks Canyon. (THW, photo)

The vertical world along the Bluff Spring Trail. (THW, photo)

One of my favorite stone clusters is on the climb above Barks Canyon. I'd sure like to be in on the conversation flowing between these standing stones and Weavers Needle.

The feature photo at the top of this post was shot just before the signed Terrapin Trail comes in from the west at 2.4 miles. Stay on the BST as it climbs east out of Barks Canyon to a low saddle at the head of Bluff Spring Canyon. Give up 180 feet while descending along the streamway to the junction with the Dutchman Trail at 3.5 miles.

Ely-Anderson Trail to Bluff Spring Mountain

The historic Ely-Anderson Trail is the best approach to the top of Bluff Spring Mountain. Carlson and Stewart dedicate several pages to the history of this trail and the surrounding area. They write that cowhand Jimmy Anderson discovered the existence of the trail in 1911. "Sims Ely knew about a legend of an unnamed mountain where Mexicans grazed horses and mules while tending to their mining activities in the 1880s. Sims Ely connected the legend to the rediscovered trail. Some people call it the Mexican or Spanish Trail." We were a little surprised to find fresh horse prints on the Bluff Spring Mountain plateau. The authors knew of experienced equestrians having problems due to steepness and exposed cliffs.

At 3.5 miles, 3,020 feet, you will come to a campsite with a large fire ring beside the BST, shown. Locate a cairn marking the start of the route on the north side of the camp. This is about 30 feet after crossing the Bluff Spring Canyon wash (there are several) and roughly 30 yards west of the Dutchman Trail junction. We regret not visiting Crystal or Bluff Spring. To reach Bluff Spring, walk north on the Dutchman Trail for less than 0.1 mile and then northwest for another 0.1 mile.

The Ely-Anderson Trail is something of a misnomer. It is a cairned route across bedrock and in the dirt the thin path is faint. Climbers should be well-practiced following cairns off-trail before undertaking this route. The cairns are mostly little piles of rocks. If you get separated from them, return to your last known rock stack and search from there. The route begins bearing north-northwest. The landscape is convoluted so the course switches directions repeatedly while following the terrain. Trust the cairns.

It is fun, even joyful, walking on sheets of tuff. The surface is worn through to the underlying white base in places, an indication of the long history of hooves and footprints on the path.

While I felt like I was walking through a well-planned rock garden, the gardener has not shown up for pruning work in a 100 years so wear long pants.

At 3,380 feet, the route bears southwest for a short distance to skirt a jumbled ridgeline. At 4.1 miles, gain that same ridge east of Point 3,790'. The route makes a 90 degree turn to the west and climbs the ridge, avoiding a large draw to the north. This image looks east at the pivot point. (THW, photo)

As you climb the mountain be sure to turn around and look through the window in Miners Needle. Passing Point 3,790', the route goes by a short section of stone wall and swings almost 90 degrees to the north-northwest at 4.3 miles. Make a mental note of this location if you are returning this way.

Now we were on the very broad expanse of the mountain. Cairns were no longer useful and the trail dispersed and disappeared. We were on our own. In this image, the highpoint of Bluff Spring Mountain is on the left. Point 4,041' is an extension of the low hill on the right. Walk northwest, either over the top or on the west side of the hill.

We topped out on low-rising Point 4,041' at 5.1 miles. It has a superb view to all points north and a unique look into Bluff Spring Mountain Canyon (a.k.a. Hidden Valley). We plotted the best route to the mountain's highpoint, shown. The slope to the summit ridge was just a little kick up. (THW, photo)

Reach the small crest at 5.4 miles. The register is inside an ammo box tucked into the large summit cairn. It was placed in 2000 and the notebooks inside hold a lot of history. (THW, photo)

The north vista is punctuated with Superstition landmarks: Palomino Mountain, Yellow Peak and Black Top Mesa, Battleship Mountain, Geronimo Head, and Malapais Mountain. The Four Peaks are off-image on the right.

West is monolithic Weavers Needle, a remnant sentinel of fused volcanic ash 400 feet higher than Bluff Spring Mountain. Shown, is the technical climbing route from the east, The Dutchman's Gold. Climbers ascend the diagonal gully that goes into the notch between the main summit block and its subsidiary. Then they climb the skyline ridge. (THW, photo)

West Ridge Route to Terrapin Trail in Needle Canyon

The West Ridge descent route is more difficult and hazardous than the Ely-Anderson Trail. While scrambling is light and I rated the exposure mild, Carlson and Stewart have tales to tell. "There is loose rock along the ridges and slopes so be careful not to slide off the cliffs. Sims Ely and others have had rock sliding experiences on Bluff Spring Mountain and all were lucky enough to be saved either by their companions or by a terrifying self-rescue." All but experienced desert mountaineers should retrace their steps to the Bluff Spring Trail. If you'd like to put in more effort, return on the Dutchman Trail, 2.3 miles further. The loop will be, in effect, a very large circumnavigation of Miners Needle.

There are some cairns on the west ridge but you are on your own with the challenges ahead. The route is pleasant enough to start. You will flank the knob (image-left) on its north and then regain the ridge. Once you reach the west-facing cliffs, improvise your bailout to the Terrapin Trail.

We tried to climb over the knob but got cliffed out and backed up.

At 3,850 feet, the ridge drops abruptly to the west. Now it gets tricky and there are several choices. We hugged the ridge as best we could while bearing northwest. Our route was not elegant but neither was it problematic. It took an hour to get from the peak to the trail. From the drop, Carlson and Stewart took a north-pointing ridge into a sizeable ravine well north of our route. They recommend staying on the north side of the ravine. We crossed a small drainage, shown, at about 3,500 feet and then rode the ridge down to the trail.

We discovered another planet in the episodic rivulet we stepped across. (THW, photo)

We intersected the Terrapin Trail due east of Weavers Needle at 6.5 miles, 3,200 feet. Your location will vary, of course. We were pretty surprised to see a tall cairn planted right there.

Heading south on the Terrapin Trail was one of my favorite segments of this hike. The path runs alongside water-polished stone. Beautiful Bluff Saddle separates the waters of Needle Canyon and Barks Canyon. (THW, photo)

The Terrapin Trail is all about sculpted stone. Don't miss this balanced rock which looks ready to topple at any moment. (THW, photo)

The Terrapin Trail ends in familiar territory at 7.7 miles. It is just 2.4 miles on the Bluff Spring Trail back to the trailhead. (THW, photo)