Travel: In a 4WD vehicle with high clearance, from Tucson, drive south on I-19 to Exit 40, Chavez Siding Road. Measure from the bottom of ramp and turn west. In one block, turn right on a frontage road toward the Tubac Transfer Station. At 0.3 mile, turn left on FSR 684 at a cattle guard. Chainfruit and silver cholla are in their element. At 3.1 miles, enter Arizona State Trust Land. At 3.9 miles, you will come to an open flat. For those climbing Diablo first, turn right on FSR 4140 and park in a small lot in 0.8 mile. For Sardina, in the flat stay straight on FSR 684. Pass shaded picnic tables and enter Coronado National Forest at 4.4 miles. Pass through an open gate and the road is squeezed between steel bar fencing. Drive up a steep, rocky hill and go over another cattle guard. Just past the Upper Puerto Tank the road splits at 7.5 miles. Turn left on FSR 684A. The road gets a lot rougher and degenerates so park at first opportunity if you have any question about your vehicle. We turned onto 684A and parked in a pullout west of the road at 7.9 miles. There is room for several vehicles. The road continues but requires a specialized vehicle.

Distance and Elevation Gain, Sardina Peak: 3.4 miles; 1,680 feet of climbing

Distance and Elevation Gain, Diablo Mountain: 2.2 miles; 1,250 feet of vertical

Total Time: 2:30 to 3:30 for each peak

Difficulty: Sardina Peak utilizes a two-track for the first mile, otherwise both hikes are off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 2 with no exposure

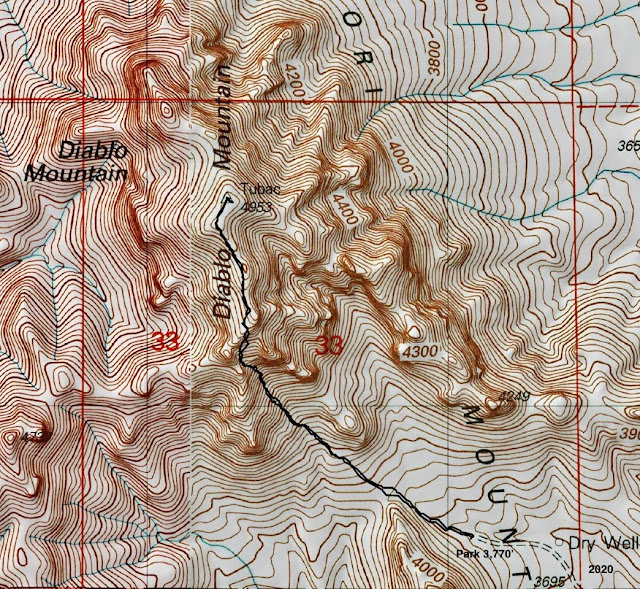

Maps: Tubac (Sardina Peak); Amado (Diablo Mountain), AZ 7.5' USGS Quads

Date Hiked: January 28, 2020

Quote: These smoky bluffs are old traveling companions, making their way through millennia. Ask them if you want to know about the true turning of history. You’ll have to offer them something more than one good story, and need to understand the patience of stones.

Joy Harjo, 2019 United States Poet Laureate

The elongated Cerro Colorado ridgeline rises northwest of companion summits Sardina Peak and Diablo Mountain. Standing on Peak 5,736', I wondered what weighty communication was forever flowing between the tan and red mountains.

Sardina Peak, 5,616'

Route: Bear southeast on a rough two-track until it sputters out on a platform at elevation 4,660 feet. Ascend southwest to gain the northwest ridge of Sardina Peak. From there, it's a straight-forward ridgeline climb to the summit.

Curious about the peak's name, I stumbled on the Legend of the Silver Bullion at Sardina Peak in Hike Arizona. The website Desert Mountaineer references Arizona Place Names (Will C. Barnes) with this attribution: "A Mexican named Sarvinia lived for years near this peak. With reference to the peak, his name gradually was anglicized to Sardina."

This was my first hike with the Southern Arizona Hiking Club and I appreciated the reverence and competence this group possessed while hiking in the desert. Further, I was grateful that they welcomed my partner and me so heartily.

The Sardina Peak hike is in three enjoyable segments: the two-track, a scant social trail to the northwest ridge, and the moderately steep pitch to the summit. It is possible to see the top of the peak from the parking pullout, elevation 4,020 feet. (Thomas Holt Ward, photo)

Hop on the road and begin ascending, gentle for now, through rolling grassland. We did not see flowering plants in January but there are a fair number of uncommon, even rare, plants in this region. We were looking at the north face of the mountain all the while.

Crest a low ridge at 0.6 mile, 4,380 feet and then give up 60 feet and cross an east fork of Sardina Canyon. The road pitches skyward at such a fierce angle we wondered how any vehicle could crawl up without flipping over backwards. This image looks down the road to the east fork and the shallow ridge.

The road ends on a platform at 4,660 feet at 1.1 miles. From here, there are multiple options to the summit. We debated going right up the north ridge but opted for what we figured was the most reasonable, and perhaps the standard route. The road pinches to a wisp of a social trail (watch carefully) that takes aim at the northwest ridge (image-right). It was exquisitely beautiful as the low rays of January sun backlit grasses with a golden sheen and turned spent sotol stalks into towers of light. (THW, photo)

By now I'd labeled this a bliss-out hike. The ridge was pretty steep but there were no obstacles to dodge. There were boulders to clamber over and yet the footing was the best I'd experienced in the Tumacácori Mountains. Patches of resurrection moss had taken hold in the bedrock.

The ridge is thin enough to create a feeling of openness but it is never scary. The visual field is expansive and, in this moment, softness rolls ever onward. (THW, photo)

The north end of the summit ridge is rounded and holds a solar powered microwave transceiver. (THW, photo)

In contrast, the south end is a jumble of angular boulders poised before a significant drop. Top out at 1.7 miles. The peak register dates back to 1999.

While the view of southern Arizona and northern Mexico is far reaching, what got my heart soaring were the peaks further south in the Tumacácori Mountains where we'd been just five days prior. Below, on the left is Tumacácori Peak with a long ridge terminating at Peak 5,687'. To its right is the highpoint in the range, Peak 5,736'. Next is Point 5,675' and then Tumac Benchmark, 5,635', on the far right.

The Tumacacori Highlands encompasses three remote mountain ranges on the United States and Mexico border just west of Nogales: Pajarito, Atascosa, and Tumacácori. Plant ecosystems are oak woodland on north facing slopes and scrub-grassland on south facing slopes. For an extensive list of the rare and protected plants growing in the region please follow the link.

Diablo Mountain, 4,953' (Tubac Benchmark)

Route: Hike northwest off-trail to penetrate the south ridge of Diablo Mountain. Hold the ridgeline to the broad summit. This topo uses 20 foot contours so the route appears steeper than it is.

This image of morning-red Diablo Mountain was taken on the roll from FSR 684. The Tumacácori and Atascosa Mountains are composed chiefly of Tertiary volcanic rocks. The Tertiary Period began about 66 million years ago with the mass extinction of dinosaurs and ended when the ice ages of the Quaternary Period began, about 2.6 million years ago. While Diablo Mountain is quite near the terminus of the range, the peak at the far north end is Diablito (Little Devil) Mountain, 4,070'.

The small parking area at elevation 3,770 feet is just south of a good-sized wash, a north fork of Puerto Canyon. We pondered the best route to the south ridge and decided to go left of the white outcrop, image-center-left, a good call.

A social trail ran for a few yards and disappeared. The mountain doesn't see many visitors and the terrain was too dispersed for a trail to naturally form. We held a northwest bearing while winding around ocotillo, mesquite, palo verde, and sotol. Looking at the image below, we went within touching distance of the multi-armed saguaro left of the draw. The ridge is troubled with buttresses. We aimed for the opening left of the central block of cliffs directly above the saguaro.

Here's a better look at the beacon saguaro.

The slope is rather steep and rubbly. Climbing, boulders formed natural stone steps but it was less stable on the descent. (THW, photo)

We were clearly on the standard track because at 4,600 feet, a social trail materialized that accessed the ridge. The track went between two trees that were holding down the ground between outcrops.

We gained the ridge at 0.8 mile, 4,800 feet. In the west, Sapori Wash is making for the Santa Cruz River. The Cerro Colorado Mountains are the next range over, and Baboquivari Peak proudly reminds all of us where we are in space and time. (THW, photo)

Ascend right on the boulder-studded crestline or just off to the side. The grade is mellow, the ocotillo are plump, the shindaggers are easily avoided. But rocks roll underfoot with a frequency that indicates this mountains doesn't see much traffic.

The thin ridge yields to a broad, softly rounded, grassy summit at 1.1 miles.

This little peak has a register and an exceptional view in all directions. Swinging around, above Tucson, Pusch Ridge rose in jagged thrusts to Mount Lemmon. Next, were the trifecta in the Rincon Mountains and then Elephant Head and Mount Wrightson in the Santa Rita Mountains. Looking south, Tumacácori Peak is on the far left, and to the right of Sardina Peak is the tallest mountain in the Tumacácori Highlands, Atascosa Peak, 6,422'. (THW, photo)

Two reference marks point to the unusual Tubac Benchmark. It isn't a typical bronze disk used by the United States Geological Survey or the National Geodetic Survey. It is stamped, "United States Army, Fort Sam Houston, Texas." Name or number and elevation were left blank. Fort Sam Houston is located in San Antonio, Texas. It is one of the Army's oldest installations, constructed in the 1870s.

The network of survey monuments has been used since 1879 and are the basis for horizontal and vertical control for all the mapping done in the United States. I found two excellent resources on the history and purpose of benchmarks: Peakbagging and SummitPost. However, there was no account of benchmarks placed by Fort Sam Houston.

No comments:

Post a Comment