Essence: Mount Ridgway is a vertical mile above the trailhead and 6.2 miles on foot. Ascend 2,900 feet over 4.3 miles just to break out of the timber where the fun begins. Trail washouts and volcanic towers and exotic features on both sides of the Weehawken Creek gorge break up the tedium. Three stunning high basins and the east ridge finish make up for the ultra long approach. The summit affords an incomparable view of the north face of Mount Sneffles and neighboring peaks. Strong, swift hikers could conceivably climb Whitehouse Mountain from the shared saddle. The hike is within the Uncompahgre National Forest. Note: For hikers living in Ridgway or other surrounding

communities, there are trip reports detailing a route that approaches

both Mount Ridgway and Whitehouse Mountain from the north saving miles and total

vertical.

Travel: From Ouray, drive south on US 550. At the first hairpin south of town, turn south on Camp Bird Road, signed County Road 361, Camp Bird Mine and Yankee Boy Basin. Measure distance from the junction. The 2WD gravel road has some potholes. Cross the Uncompahgre Gorge at 0.2 mile and drive southwest up Canyon Creek. Cross the river at 1.9 miles. Weehawken Trailhead parking is on the right at 2.6 miles, just before Thistledown Campground. There is room for three vehicles.

Travel: From Ouray, drive south on US 550. At the first hairpin south of town, turn south on Camp Bird Road, signed County Road 361, Camp Bird Mine and Yankee Boy Basin. Measure distance from the junction. The 2WD gravel road has some potholes. Cross the Uncompahgre Gorge at 0.2 mile and drive southwest up Canyon Creek. Cross the river at 1.9 miles. Weehawken Trailhead parking is on the right at 2.6 miles, just before Thistledown Campground. There is room for three vehicles.

Distance and Elevation Gain: 12.4 miles; 5,300 feet

Total Time: 8:00 to 10:30

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation challenging; Class 2+ with no exposure

Maps: Ironton; Ouray; Mount Sneffles, Colorado 7.5' USGS Quads

Latest Date Hiked: September 30, 2024

Quote: A journey of 1,000 miles begins with a single step. Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation challenging; Class 2+ with no exposure

Maps: Ironton; Ouray; Mount Sneffles, Colorado 7.5' USGS Quads

Latest Date Hiked: September 30, 2024

Quote: A journey of 1,000 miles begins with a single step. Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

The summit of Mount Ridgway is revealed at last upon alighting on the saddle west of Point 13,150'. From there it is a playful 0.3 mile scamper up the east ridge to the crest, image-center-right.

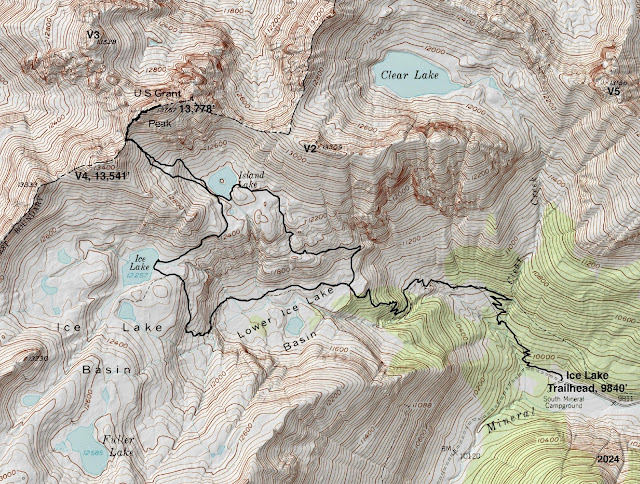

Route: Hike northwest on the Weehawken Trail to its end. Ascend on a social trail southwest to timberline at 11,420 feet. Off-trail, hike north through two alpine basins to the Mount Ridgway-Whitehouse Mountain basin. Pitch northwest in an open gully to the saddle west of Point 13,150'. Climb the east ridge to the summit.

Personal Note: We summited Mount Ridgway on our second attempt. On September 5, 2024, we made it to elevation 12,100 feet before turning back. We hadn't allowed enough time, the weather threatened, and unable to get a visual on the summit, we were confused about navigation. On our second hike, the leaves had turned gold and the chance of precipitation was 3%. We got most unlucky. We came for the views but a graupel storm blew up on the summit ridge and surrounding peaks were shrouded in snow clouds. However, we did dial the route which I am pleased to share with you. Lamentably, we planned to return on the south ridge but the weather discouraged new exploration so we retraced our steps to the trailhead.

Weehawken Trail #206 begins down in the Canyon Creek corridor at elevation 8,740 feet and ends in 3.7 miles beside Weehawken Creek at elevation 10,760 feet. Judging from almost indecipherable overgrown tree blazes, the Weehawken is a very old trail. It sustains a pleasant grade and is well maintained. In fact, we spoke with a large Civilian Conservation Corps crew clearing felled trees, building log steps, and adding water drains.

Please sign the trail register a few paces up the trail. The footpath switchbacks up the hillside bearing northwest and staying north of Weehawken Creek. Towering cliffs and walls enclose the gorge. Below, Point 12,578' is the grassy rise southeast of Canyon Creek. Thistledown Creek separates it from the crags extending north from Hayden Mountain. (Thomas Holt Ward, photo)

We ambled up through a mixed forest, light filtering through battery powered aspen. The Gambel oak had spun a variegated autumn tapestry. Droplets of water glistened on yellow leaves scattered on the slender, dirt path.

(THW, photo)

At the conclusion of the first set of switchbacks, 1.6 miles, 9,900 feet, the trail to the Alpine Mine Trail Overlook splits off the Weehawken.

After the junction vegetation was growing in the path, suggesting a lot of hikers divert on the Alpine Mine Trail. The Weehawken essentially holds to the contour with some undulating. The thin trail platform is dug into the steep hillside, at times off camber.

At 1.9 miles, 10,160 feet, the trail was washed out by a significant side creek. Cairns guided across the mess and it was easily traversed, shown. We counted 28 side channels between here and trail's end in the first high basin. Let the obstacle course begin. We hopped easily across some. But others were ravines with great masses of boulders and vertical banks where torrents had bombed out the trail. The crossings slowed down progress in both directions. It's hard to make time on this trail. (THW, photo)

The tedium was interrupted by weathered volcanic pinnacles and spires on both sides of the creek. The striking monolith on the south wall of Weehawken Creek is Point 12,571'.

Pass by the trail to Weehawken Mine at 2.2 miles. The track switchbacks up to 10,400 feet, finally making some elevation. In this convoluted, wholly volcanic realm, it's easy to see why the trail is constantly obliterated.

Pass under a cluster of tall, free-standing needles while crossing a wide, braided channel at 3.5 miles. This is the marker for the approaching end of the Weehawken Trail.

At 3.6 miles, 10,760 feet, the trail divides at a large, stacked cairn, shown. The left thread terminates in a few yards at the creek. A wooden sign, "Weehawken Creek," marks the official end of the Weehawken Trail. For Mount Ridgway, double back to the big cairn and take the right branch at the split. The social trail is not engineered and there are some unmitigated steep pitches. We were happy to have the tertiary trail. We weren't climbing Ridgway without it.

The photo below was shot as we emerged from the woods. The trail is pressed under and against an immense volcanic wall bifurcated with countless chutes shedding water and rock.

The trail unceremoniously ended as we broke out into an immense and exquisite high alpine basin at 11,420 feet. The elation was immediate payback for the long slog through the timber. We'd already hiked 4.3 miles and climbed 2,900 feet. Craggy points 12,571' and 12,857' enclose the basin on the southeast rim.

A rock glacier extends into the center of the basin. It is material exfoliated from the northeast ridge of Potosi Peak, 13,793', image-center-left.

Heading the basin is Coffeepot, image-center. On its right is the east ridge of Teakettle Mountain. The spire just visible, image-right, is the highpoint of Teakettle. Both peaks are fifth class and are typically climbed from Yankee Boy Basin. Even with topographical maps in hand and decent map reading skills, on our first trip we weren't sure what we were looking at or how to proceed to Ridgway which is not visible from this basin. Turns out, this is the first of three basins to be traversed on the way to Mount Ridgway. On our second, successful attempt we dialed the route. To start, stay on the right side of the drainage until you are just past the trees then curve on up to the north.

Climb the rounded ridge, image-center, and intercept a social trail at 4.7 miles, 11,860 feet. The trail is sporadic but useful.

Let the trail carry you to the rim of the second basin at 4.8 miles, 11,960 feet. Regardless of whether you are on the elusive trail, your next objective is to top the north rim of this basin at precisely 12,300 feet. Looking below, Whitehouse Mountain is image-right. You want to hit the ridge at about image-center.

The basin floor is split by a series of soft swales. Head them or simply cross them. The highpoint seen in this image isn't the crest of Ridgway but it is the first bump on the ridge south of the peak.

We gained the basin rim at 12,300 feet below weathered volcanic hoodoos.

To the immediate north is Whitehouse Mountain, 13,500', climbed from the saddle east of Point 13,150'.North of Whitehouse is Corbett Ridge, 13,107', typically climbed from the north.

The

trail is exceedingly helpful contouring across a steep slope into the Ridgway-Whitehouse basin interior.

The social trail is headed for the Ridgway-Whitehouse saddle east of Point 13,150'. While you could mount the shallower gully, Roach cautions hikers to "avoid the pesky traverse of Point 13,150'." Rather, leave the trail at about 12,560 feet and consider how you will attack the open slide.

Our ascent route was pretty horrible but our descent route was infinitely easier and safer. Going up, the footing was good to start but then we were too far north, up against the wall. It was so steep, the rocks and me were at the angle of repose. I kept sliding downhill along with all the material and it took great power and strength (and nerve) to propel upward.

Instead, from where the trail to Whitehouse splits, stay in the middle of the slide to the point of greatest constriction, shown. Then head for the south side of the gully and look for a wildcat track in the soft sandy soil. Butt up against the gray outcrop on the left. When the wall diminishes, mount the east ridge at the low point west of Point 13,150'.

Deep into the hike, the summit is finally visible, image-center. The remaining 0.3 mile to the highpoint is pure pleasure on angular, stable talus. (THW, photo)

The weather blew up out of nowhere and we got pummeled with graupel. We took shelter at the base of the short cliffband encircling the summit. At first opportunity we located an easy, Class 2+ scramble on the south side.

We walked up the summit mound on small talus plates.

Crest the flat, elongated Mount Ridgway summit at 6.2 miles after 5,200 feet of vertical. (THW, photo)

Mount Ridgway had been on my wish list for about 15 years. My primary desire was to see the north face of Mount Sneffles, 14,155', Colorado's 27th highest peak. While the view was shrouded, the scene was nevertheless surreal, even sublime. The chromatic field was, in painter Paul Cézanne's words, "The colours of things that rise up from the roots of the earth." Cirque Mountain, 13,692', was a wall of dusky violet. Its stilled rock glacier was folded in a fluid pigment of gray-green lichen. Tundra was cast in wrought iron and gold.

Our plan was to explore the south ridge, shown, and exit at the Teakettle Mountain 13,020-foot saddle. But the weather was even worse south of the peak so we headed back as we came. From the left are Potosi Peak, Coffeepot, and Teakettle Mountain.

I am tempted by Whitehouse Mountain and its tabletop that goes on forever. If we return, we'd likely approach the saddle east of Point 13,150' from the basin on the north.

Looking north across rippling yellow is Lake Otonawanda, the Uncompahgre River Gorge, the town of Ridgway, and Grand Mesa.

We descended in forgiving soil against the gray wall. There were no fresh footprints but there were clear signs of use.

We got back on the social trail and were amused by the classic upper basin boulder field. This is where all the big boys who exfoliated off Whitehouse hang out. (THW, photo)

The trail into the second basin comes and goes. We crossed the swales as before. The fierce and foreboding north faces of the peaks contrasted markedly with gentle slopes where soil and flora managed to take hold.

Counterintuitively, there is more red in the high alpine in the fall than in any other season. As royal blue gentian signal the end of summer, the scarlet leaves of alpine avens proclaim the advent of autumn.

This image was shot as we dropped into the first basin. It looks up at the Teakettle-Ridgway saddle, the escape route from the south ridge. It looks incredibly appealing. If you have the opportunity to explore the south ridge please leave a comment and tell us your story. (THW, photo)