Travel: I have been on all the roads to White Pocket. Following is the easiest route. You will need 4WD, high clearance, and a lot of patience. From mile marker 25.7 on U.S. Route 89, about five miles west of the Paria Contact Station, turn south on House Rock Valley Road. Zero-out your trip meter. Pass the Wire Pass TH at 8.4 miles and Stateline Campground at 9.9 miles. On a decent dirt road, pass Lone Tree, road 1079, at 16.4 miles. (Yes, you can get there from Paw Hole but I've gotten stuck every time by deep sand on a steep incline.) Turn left/east at 20.2 miles. The sign for 1017 is just up the road. At 23.3 miles, stay straight. Here, 1066 (1081 on some maps) veers left, a primitive road experience. Pass 1085 at 26.4. In just another 0.1 mile, at 26.5 miles, bear left on 1087. This is Pine Tree Pockets with a cluster of old ranch buildings and a corral. (Note: In 2019, I learned that travelers have been rerouted around the ranch to the right. Signs will lead you back onto the proper road but my mileages are likely inaccurate.) At 30.5, bear left on 1086. Open and close a rickety barbed wire fence at 30.9 miles. At 32.9 miles see White Pocket Butte. At 34.5 miles, 1323 comes in on the left from Poverty Flat and Cottonwood Cove. At 35.4 miles stay straight. Reach the trailhead at 36.0 miles. The large lot is suitable for camping but a better site is at road's end, a half mile further. No water, no facilities. Trails Illustrated No. 859 will help you find the TH. Allow two hours from Hwy. 89.

Distance and Elevation Gain: 3 to 8 miles; 7 miles for the route on the map below; 500 to 1,500 feet of climbing, it's up to you

Time: 3:00 minimum; all day is optimal

Difficulty: Off-trail; navigation easy; mild exposure on The Butte to the ridge of ocher towers

Maps: Poverty Flat, AZ 7.5 Quad; Trails Illustrated: Paria Canyon, Kanab No. 859

Latest Date Hiked: October 10, 2015

Quote: I've always regarded nature as the clothing of God. Alan Hovhaness, American composer

Allow curiosity to dictate your way in fanciful White Pocket. (THW, photo)

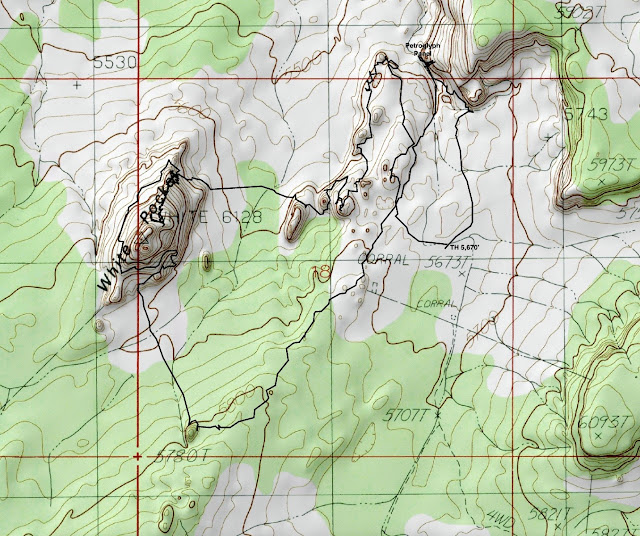

Route: There is no defined route. Below is a copy of our GPS track. After meandering among lower elevation features, map-center, we climbed the north ridge of The Butte before circumnavigating the escarpment. Lastly, we discovered a petroglyph panel at the northeast edge of White Pocket.

A wide, sandy path bears west from the parking lot, elevation 5,670 feet. An informative placard explains that this region was once covered in shifting sand and complex dunes. Today's cross-beds are solidified windblown deposits. It is less than 0.2 mile to the rock and there ends any notion of a trail. Instead, we spend the day walking on exhumed desert sand dunes. Standing here, we decide to climb the camel hump, image-right, and have a look around.

The dominant elements at White Pocket are globular mounds of polygonal white Navajo Sandstone, the most prominent rock layer exposed by uplift and erosion on the Colorado Plateau. Cracks and fissures are produced by tensile stress and exposed by weathering. These features make scaling even steep pitches easy. (THW, photo)

The highpoint, what regulars call The Butte, is magnetic. But first, as indicated on the map, we enter the stony dunefield. Weaving here and there, propelled by wonderment, we explore the perplexing, intricate labyrinth.

Frozen curlicues and whorls, cell patterns, fins, and cross-bedding are mesmerizing. The bizarre nonsensical pandemonium was formed before the sand became rock in a process called soft sediment deformation. White Pocket is simply strange, strengthening its appeal.

This area is a maze so be sure to get lost. Every dead end yields a mind-altering vista. (THW, photo)

Ivory, apricot, rust, and brick, are intermingled with overlying white rock. The color palette is attributed to iron-bearing minerals within the sandstone. (THW, photo)

Topping out on the tallest globular biscuit, this is the view east toward the bluff with the petroglyph panel tucked at its base.

West is The Butte. Climbing the north slope is not for everyone. However, circumnavigating the escarpment yields even more mind-boggling features.

Follow the fence line to the monolith. The barb wire barrier is collapsed at the east wall.

Upon reaching the north slope, ascend the red cross-bedding using nature's stone switchbacks. Friction up the grey sandstone pitch. There are plenty of climbing features; sticky shoes are helpful. (THW, photo)

Pass by an unexpected and undisturbed live sand dune. Top out on the ridge of ocher towers, shown. (THW, photo)

Pictured is one of several towers on the east-west running ridge located north of the highpoint. We clamor up two of the tiny saddles between towers. The drop on the south side is precipitous.

The image below shows the summit of The Butte at center, less than 100 vertical feet above our point. We learned later that it may be possible to scoot around one of the towers and into the bowl to the south. Then scale what looks like an improbable pitch to the summit. It is very exposed. (THW, photo)

We circumnavigate The Butte while scouting for another route to the top. We descend the north slope and cut west through a weakness in the ridge. The landscape is dazzling. Walking south, we simply follow the shifting, natural sidewalk. The west side is characterized by massive fins and row upon row of stone scallops.

The angular south end has butter-smooth, vertical walls streaked with color. A Utah-blue sky holds the land in place. (THW, photo)

We walk east through scratchy plants to a small, well-defended knob. From this perspective, The Butte is armored with an encircling barrier wall. In the image below, the ridge we scaled is on the right.

To locate the petroglyph panel, walk to the bluff at the northeast edge of White Pocket. The panel is located on the outside wall of a ground level alcove just before the fence line. Etched into desert varnish are bighorn sheep, deer with elaborate racks, small anthropomorphs, and sharpening grooves or counting slashes. Soot ceilings indicate this was a dwelling site. (THW, photo)

"White Pocket" is a curious name. Perhaps it references the swath of sandstone bubbling out of the piñon-juniper and sage-blackbrush flats.

3 comments:

Hi Deb, Vagabond Jeff here, from Baja Hikers. Donna and I went to White Pocket last year based upon your directions. Your directions were right on getting there and it was a spectacular place. Love your website/blog and hope to see you and Tomas down the road. Jeff Hale

Jeff! I am delighted to hear from you. First, I'm relieved to know you were able to follow my complicated directions to White Pocket. I've been thinking of you and Donna because I am in Tucson for about three weeks and want to do the Supers Traverse (Ridgeline Tr) and Sombrero. You took me on both of those hikes. Tomas and I will be watching to see if you post a hike while I'm in AZ. Debra

This was a truly amazing place!! I hadn't planned on it, but between a friend's recommendation and then finding your blog and some other sources for White Pocket, I decided it had to be one of the only 4 days I had exploring the area this trip. Thank you!

I didn't want to rent a 4x4 vehicle, so instead I took a guided tour to White Pocket on Wednesday, and I was constantly in awe! Having the guide provided some additional tidbits relating to the human history in the area - the name, for example. Because this area was (and technically still is, for those grandfathered in) ranch land, water sources for the cattle was an important factor in determining where to send the herd to graze. Areas in the rock that can hold water are referred to as "pockets", and then named based on the terrain in which they are found. Ranchers later built an earthen dam at the pocket, and unfortunately this restricted water flow to the point where the water became stagnant with bugs and bacterial, and no longer fit for cattle. There erosion evidence from the cattle trail over the rock from the grazing lands to the pocket.

Post a Comment