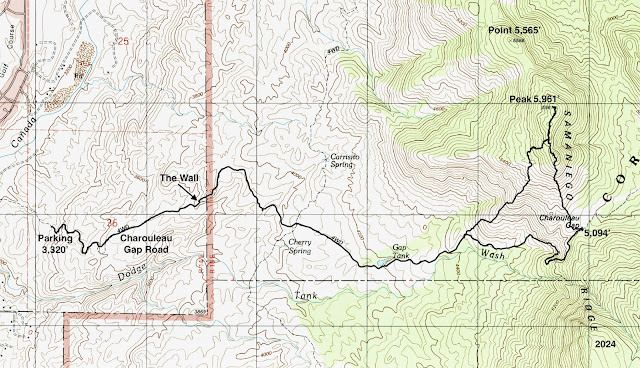

Essence: Peak 5,961' is the highpoint on a northern extension of Samaniego Ridge. Probe into the northernmost quadrant of the Santa Catalina Mountains, expanding your home ground. Drive and/or hike 6.5 miles to Charouleau Gap. From there, the summit is one mile north off-trail with 900 feet of vertical. View the northern ramparts of Mount Lemmon, Samaniego Peak, and Oracle Ridge. Westward, the range splays out onto the desert floor in Oro Valley. The suggested alternate descent route features sheets of weathered Catalina granite and spheroidal boulders. The road to Charouleau Gap is equivalent to being on a trail. The technical 4WD track is trenched and has solid rock moguls. Crushed granite on bedrock is slick for the hiker. This description begins two miles out the Gap road on Arizona State Trust Land. Most of the hike is in Coronado National Forest. LiDAR increased the peak's elevation by one foot to 5,962'. The saddle at the Gap measures 5,094' and the rise is 868 feet.

Travel: From AZ 77 in Oro Valley, turn east on paved Golder Ranch Road and measure distance from there. At 1.1 miles turn left on Lago del Oro Parkway. The mountain and Gap are visible from the road. At the top of a rise, 4.2 miles, turn right into a large dirt OHV lot with placards. 2WD vehicles must park there. High clearance, 4WD low, and beefy tires are required to park two miles out the narrow road. Beyond that, a specially modified vehicle is required. Cross two stream channels and Cañada del Oro at 1.4 miles. Do not attempt to ford in high water. Park in a tiny pullout with room for one vehicle at 2.0 miles. Display your State Trust Land permit.

Distance and Elevation Gain: 10.0 miles; 2,800 feet (Starting 2.0 miles out the Gap road.)

Total Time: 5:30 to 7:00

Difficulty: 4WD road, off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 2 with no exposure; hike on a cool day and carry more water than you think you will need.

Map: Oracle, AZ 7.5' USGS Quad

Total Time: 5:30 to 7:00

Difficulty: 4WD road, off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 2 with no exposure; hike on a cool day and carry more water than you think you will need.

Map: Oracle, AZ 7.5' USGS Quad

Reference: A Guide to the Geology of Catalina State Park and the Western Santa Catalina Mountains, by John V. Bezy, Arizona Geological Survey, Down-to-Earth No. 12, 2002.

Date Hiked: November 26, 2024

Quote: Nature is not a place to visit. It is home. Gary Snyder

Date Hiked: November 26, 2024

Quote: Nature is not a place to visit. It is home. Gary Snyder

We've covered a fair amount of territory in the Santa Catalina Mountains and yet Peak 5,961' rested in obscurity until a friend said she could see the mountain from her home in Oro Valley. If you are partial to granite, place this piece into your embedded landscape puzzle.

Route: Either walk or drive east on Charouleau Gap Road. While we parked at 2.0 miles as indicated on the map below, some vehicles may make it to The Wall at 3.3 miles, or even to the Gap at 6.5 miles. From the Gap hike north to the summit. Return as you came or divert west on a granite slope and then southwest on a ridgeline back to the incoming road.

We started hiking from the tiny pullout, elevation 3,320 feet. This image was shot from parking. Beyond, stone moguls, and sheets of solid rock will be problematic for most vehicles.

Route: Either walk or drive east on Charouleau Gap Road. While we parked at 2.0 miles as indicated on the map below, some vehicles may make it to The Wall at 3.3 miles, or even to the Gap at 6.5 miles. From the Gap hike north to the summit. Return as you came or divert west on a granite slope and then southwest on a ridgeline back to the incoming road.

We started hiking from the tiny pullout, elevation 3,320 feet. This image was shot from parking. Beyond, stone moguls, and sheets of solid rock will be problematic for most vehicles.

Catalina granite is a plutonic mass of igneous rock that formed when magma cooled and crystallized underground. It is widely exposed on the west flank of the Santa Catalina Mountains. Peak 5,961' is composed entirely of Catalina granite, a homogeneous, non-layered rock made up of tightly interlocking quartz, feldspar, and mica crystals. Large crystals are visible throughout the great sweeps of rock. As the rock disintegrates it leaves granular gravel called grus on the surface. It is intensely slippery! All three of us lost our footing walking back down the road.

We had the road entirely to ourselves, no hikers, no motos. Generally, hiking up a road can be a letdown. But the Gap road presented more as a trail as we traversed across the stone quiet desert. (Thomas Holt Ward, photo)

As we gradually rose into the foothills, we were accompanied by the usual Sonoran flora mix--saguaro, mesquite, pricklypear, and ocotillo. We passed by dozens of granite islands sculpted by weathering and erosion into distinctive and resistant landforms called domed inselbergs.

A corridor with vertical sides leads to The Wall at 1.3 miles, 3,860 feet.

The Wall is a ten to twelve foot lift. A local riding a Yamaha YZ250 caught up with us in the Gap. He was able to bust up The Wall, taking it just right of center. (THW, photo)

Cross the boundary between State Trust Land and Coronado National Forest shortly beyond The Wall at a cattle guard. The ultra cool welded sign reads, "Charouleau Gap, 4 Wheel Drive Trail maintained by the Tucson Rough Riders in cooperation with the United States Forest Service, 'Adopt-A-Trail.'"

We had no regrets walking the road. On our return, the silhouettes of peaks we'd explored in the Pusch Ridge Wilderness were lined up from Pusch Peak (image-right) to Cathedral Rock.

Looking east, more granite hills precede Samaniego Ridge. As you close in on the Gap there are excellent views of Mule Ears, points 7,022' and 7,435', and distinctively tapered Samaniego Peak.

At 2.2 miles cross the primitive track shown on the Oracle quad. Gap Tank, 2.8 miles, was a dry bowl of fine, gray dirt fluffed up with tire tracks. The road circles a bowl above Dodge Wash, swings sharply northeast and takes direct aim at the Gap. Below, the false summit of Peak 5,961' is graced by a mantle of white gold grass. (THW, photo)

If you parked two miles out the road as we did, reach Charouleau Gap at 4.5 miles, a reasonable distance. If you started from the parking lot off Lago del Oro, you've already pounded out 6.5 miles, whew--it's going to be a big day. Before LiDAR, I would have extrapolated the saddle's elevation at 5,100 feet. The LiDAR measurement, supposedly accurate to within four inches, reads 5,094 feet. The Gap road continues east, drops into the inner Cañada del Oro, and then continues to Oracle for a total of 19 miles. (THW, photo)

While we were taking a break on the saddle, the motocross rider from the immediate neighborhood met up with us. While he was an experienced rider, this was his maiden run on the YZ250. Impressive. (THW, photo)

On our most recent visit to Samaniego Peak in 2018, we were tempted to carry on to Mule Ears. However, we were dissuaded by The Santa Catalina Mountains: A Guide to the Trails and Routes, by Pete Cowgill & Eber Glendening (out of print). In the most recent edition (1997), they wrote the trail was nearly overgrown with dense brush and was difficult to follow. They stated it was more of a route than a trail way back then. (THW, photo)

The route to the summit is obvious. We crossed back west over the cattle guard then mounted the subtle, rounded south ridge. The climb was pleasant, grassy, not too steep, not too thorny, not too rocky. We easily swerved around patches of beargrass and Arizona oak.

After crossing a barbed wire fence the slope pitched but footing was good as we chased after the false summit.

This image looks back on the Gap and the location of the elusive Samaniego Ridge Trail. (THW, photo)

Boulders were tightly bunched as we approached the false summit. Now we were getting to the best part.

There is a minor cliff on the north side of the false summit but go stand on top before bypassing on the west. The roller is composed of gigantic weathered boulders and a perfect sphere. How on earth?

Crest the false summit at 5.1 miles, 5,900 feet. On the very top the bedrock has been divided into compartments. According to geologist John Bezy (see the reference at the top of the post), the joints could have formed as the molten granite cooled and contracted. Or, the earth's crust might have faulted and folded after the rock was in place. At any rate, sets of joints intersect other joints at various angles and create rock boxes. Check it out. A second roller stands between the false summit and the peak.

The only aggravation on the hike was the abundant agave. It busted up our lines, sent us dodging. No matter how hard we tried, we all got poked time and again. There was some boulder hopping and deflecting as well but that's pure fun.

It is moments like the one shown below that make this seldom visited mountain so exceptional. (THW, photo)

Boulders moderate on the final rise to the summit. There is evidence that the Bighorn fire swept across the mountain. It burned almost 120,000 acres in the Santa Catalina Mountains in July, 2020.

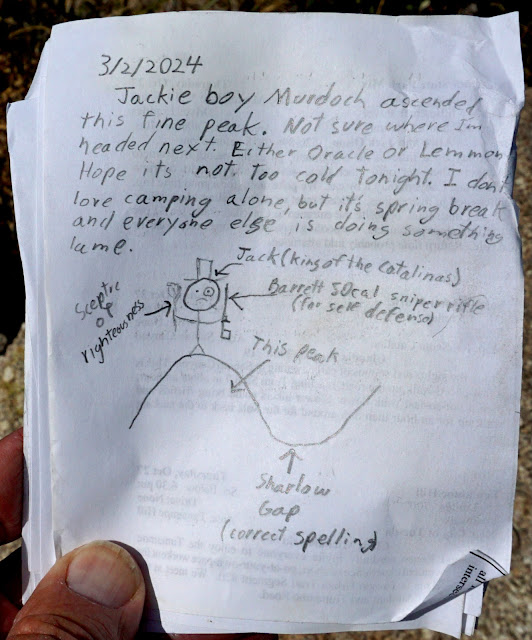

We crested the peak at 5.5 miles. The highpoint is rather indistinct among all the big boulders. The summit register, dating to 2002, is buried in the peak cairn. We were amused by a recent entry. I wouldn't be surprised to learn locals call the saddle "Sharlow Gap." (THW, photo)

We contemplated dropping down the north ridge to Point 5,565' (shown) and going on out to the final roller. I have to believe it is wildly beautiful. But the 500-foot drop was complicated by boulders and brush so we abandoned the idea. The collection of white buildings seen below is Biosphere 2 located in Oracle and operated by the University of Arizona.

Northwest is Oro Valley and unmistakable Picacho Peak. To its east, Newman Peak is the highest point in the Picacho Mountains.

Below, Mule Ears is image-left. Point 7,435' is almost eclipsing Samaniego Peak. Even Baboquivari Peak is visible beyond Pusch Ridge.

Samaniego Ridge is separated from Oracle Ridge by Cañada del Oro, the principal watercourse draining the north slopes of Mount Lemmon. Yes, the very arroyo we crossed on the way to the Gap. It hooks an about-face around the north base of our mountain. All three peaks shown, Marble, Rice, and Apache, can be traversed in one long day on Oracle Ridge.

As we were leaving the peak we decided to see more of the mountain by diverting from our ascent route. We left the ridge at 5,860 feet (shown) and descended southwest, aiming for the road. This was a superb decision. The first 300 feet were pure joy as we walked down the granite slope upon which perched massive spheroidal boulders.

So, how did they get there? John Bezy writes that the spheroids are characteristic of many granite landscapes. I always assumed they'd tumbled from a ridge long ago, but no. They are the remnants of curved sheets of granite that once formed the outer layers of inselberg domes. Weathering and erosion reduced the sheets to individual angular slabs of rock that were rounded by prolonged exposure to the atmosphere, disintegrating crystal by crystal. Boulders that form on steep slopes eventually succumb to the pull of gravity and roll to the base of the domes.

We came across a pricklypear with the biggest pads I've ever seen. It was growing from a patch of resurrection moss, of course!

We threaded sheets of stone creating a granite highway.

While the rock surface was sticky, the slope was steep enough to be a respectable friction pitch. My friend's boots cut loose and she did a full-body slide for 15 feet before halting, tangled up in a shrub. She suffered some serious rock rash.

By about 5,560 feet the surface granite had run its course. (THW, photo)

We turned south and lit upon a southwest bearing ridge. From there it was a practically effortless descent.

To the south we could see the one dominant switchback on the Gap road. We saved almost a mile on our shortcut. (THW, photo)

We intersected the road at 4,460 feet. The ridge we came down is image-center.

This image was shot from the parking lot off Lago del Oro Parkway. Charouleau Gap is on the far left and Samaniego Peak is image-right. Although this is a beautiful picture, you have to get out there on foot for the wondrous features of this landscape to be revealed.