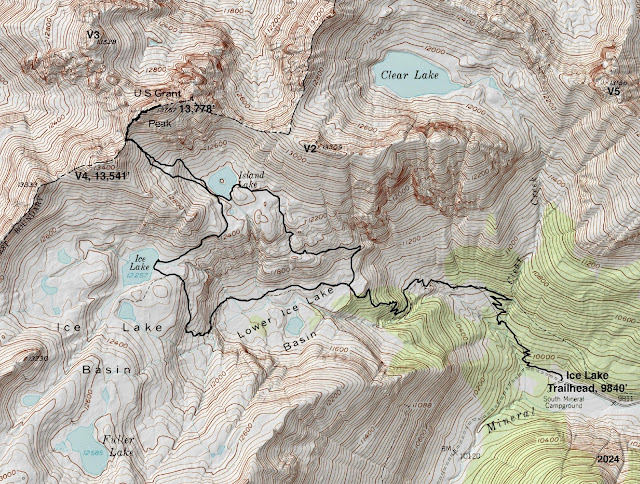

Essence: Ulysses S. Grant Peak is a raw-boned behemoth presenting a diversity of terrain and challenge for the climber. The standard southwest ridge route includes a 15-foot, Class 4 wall, a crumbling 60-foot-long ledge with catastrophic exposure, and an 80-foot chute filled with golf ball-size scree. Ranked 119 in Colorado, this bicentennial is composed of San Juan Explosive Volcanics--not exactly confidence inspiring. I have climbed "Grant" twice, each time with two other experienced mountaineers, the ideal group size. There are numerous trip reports from climbers who combined Grant with V4 and V2. Please see the cautionary note on the east ridge route later in this post. Everything about this loop as described is mythical--unraveling the route up a disordered mountain, the shimmering waters of Island Lake, ethereal blue Ice Lake, and the view of nearby peaks ringing the Ice Lake Basin. LiDAR has increased Grant's elevation to 13,778' with a rise of 734 feet. The hike is within the San Juan National Forest. The southwest ridge is on the boundary with the Uncompahgre National Forest.

Travel: From Silverton drive north on US 550 toward Ouray for two miles. At the sign for the South Mineral Campground, bear left onto a good dirt road. In 4.2 miles, park in a large lot on the right at the trailhead. There is a pit toilet but no water. The parking lot fills at dawn during the summer.

Travel: From Silverton drive north on US 550 toward Ouray for two miles. At the sign for the South Mineral Campground, bear left onto a good dirt road. In 4.2 miles, park in a large lot on the right at the trailhead. There is a pit toilet but no water. The parking lot fills at dawn during the summer.

Distance and Elevation Gain: 9.0 miles; 4,100 feet. The Ice Lake loop adds 0.8 mile.

Total Time: 6:00 to 8:30

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 4 with serious exposure; helmets recommended.

Map: Ophir, Colorado 7.5' USGS Quad

Latest Date Hiked: September 25, 2024

Total Time: 6:00 to 8:30

Difficulty: Trail, off-trail; navigation moderate; Class 4 with serious exposure; helmets recommended.

Map: Ophir, Colorado 7.5' USGS Quad

Latest Date Hiked: September 25, 2024

Quote: Achieving the summit of a mountain was tangible, immutable, concrete. The incumbent hazards lent the activity a seriousness of purpose that was sorely missing from the rest of my life. I thrilled in the fresh perspective that came from tipping the ordinary plane of existence on end. Jon Krakauer, Into Thin Air

In my 2012 field notes, I described Ulysses S. Grant Peak as, "massive, spectacular, and scary." This image of the southwest ridge route shot from V4 in September of 2010 confirms that assessment. However, for climbers with a high tolerance for exposure and chossy rock, Grant offers an exhilarating, even joyful quest. (Thomas Holt Ward)

Route: Walk generally northwest on the Ice Lake Trail for 2.2 miles. Transition onto an unsigned footpath bearing northwest to Island Lake. Off-trail, ascend to the V4-Grant saddle. Pitch northeast to the summit with some assist from a braided social trail and periodic cairns. Return as you came. Or, near the Island Lake outlet, take the link trail to Ice Lake. From Ice Lake, hike on a popular, heavily trodden track back to the trailhead.

There is a sign for the Ice Lake Trail at the northwest end of the parking lot at elevation 9,840 feet. I am assuming that if you are climbing Grant, you are intimately familiar with this trail so I won't belabor the initial description, described elsewhere in Earthline. At 0.9 mile I always leave the trail on a short, right spur to see the Clear Creek cascade, an important tributary of South Mineral Creek. (THW, photo)

Our hike in late September synced with iridescent autumn color, such a fleeting, ephemeral moment. (THW, photo)

Assuming Grant is not already under a mantle of snow, autumn is the ideal time for this hike. Monsoonal activity has waned leaving one free to relax into the hike, and the crowds visiting Ice Lake have gone home. (THW, photo)

The trail enters a thick stand of mature conifers at 1.6 miles. In this forest the Hardrock 100 course comes in from the left and joins our route to Island Lake. At 2.2 miles, 11,420 feet, at the east end of Lower Ice

Lake Basin, turn north on the secondary trail to Island Lake. Just a few years ago this unsigned juncture was faint and easy to miss. Now, it is pounded and impossible to overlook. The image below was taken

from the start of the trail.

The track begins due north then turns briefly northeast to contour across a

hillside under a cliff band. Once past this obstacle, the treadway switches due west. In the west, the geometric triumvirate that heads the Ice Lake Basin

commands attention. Pictured

are Fuller Peak, Vermilion Peak, and Golden Horn. Vermilion, 13,909' (LiDAR), is ranked 76th highest in Colorado.

Round a corner and take in the first look at guardian Grant. In mid-summer this scene is dominated by riotous wildflowers competing with Grant for attention. In late September, there are no flowers to distract. They have literally gone to seed and to sleep, and the earth is quieting down. The ground has a uniform golden red-rust cast that blends beautifully with the hue of the mountains. Only the sky and lakes contrast. The landscape is elemental and flawless.

Arrive at Island Lake at 3.4 miles, elevation 12,400 feet. Its waters are typically the clearest when summer rains have past. Below, notice the trail doing a rising traverse to Swamp Pass. From there, V2 is a quick jaunt to the east.

(THW, photo)

The southwest ridge climb to Grant begins from the 13,220-foot saddle, image-center. The ascent to the saddle is not as steep or as difficult as it appears.

Cross the lake outlet and pick a route that appeals to you for the half-mile, 820-foot climb. We went up toward the left side of the initial grassy mound and came down on the right near the inlet stream. But it matters little. (THW, photo)

The last 300 feet are in softer, gravely soil--the perfect arena for plunge-stepping on the descent.

Gain the V4-Grant saddle at 4.1 miles. There's a catch-your-breath westward view of the Wilson group of fourteeners. Snow on the north slope route to V4 ruled out climbing it this late in the year. (THW, photo)

The summit of Grant is 0.4 mile away, with about 560 feet of vertical remaining. Get on the social trail and stay on it. There are a few braids so watch carefully for cairns at critical junctures.

Fractured rock is chossy throughout the climb.

Get a taste for exposure right away. The loose rubble pile is complicated. The trail weaves back and forth dodging towers and small obstacles. (THW, photo)

The scree is slippery but the danger factor is mitigated by a reasonable slope angle.

At about 13,400 feet we came to a series of stone mounds with several workable slots. We squeezed through one chute on our way up and another on our return.

Go through a gate with ten-foot towers on either side at about 13,620 feet. It precedes the 15-foot, Class 4 crux. Actually, there are three significant challenges from here to the summit that could be considered cruxes. Take your pick. The second, the deteriorating and exposed ledge, is visible in the image below. (THW, photo)

This photo was shot on our return. It shows the gate with its perfectly human-sized opening. (THW, photo)

I stashed my poles at the bottom of the wall and didn't wish for them for the remainder of the climb. Below, my son is preparing to mount the wall, calculating his moves.

The rock is stone solid. However, holds on the lower half are skimpy. The toe holds are especially meager and shallow.

Both hand and foot holds are more generous on the upper half. Watch your head when you reach the landing or you'll smash into the overhang!

Descending, I needed a spot and I handed my pack off to my partner who was poised at the half way point. You may wish to carry a line. Caution, the crux landing is at a pinch in the ridge that falls off on either side.

The long, suspended ledge traverse begins at the top of the wall. For me, this was the most dangerous part of the entire climb. A slip would be fatal. Pieces of the ledge have sloughed off since we were there in 2012. In fact, trip reports as recent as 2020 claim the ledge was comfortably wide. I know many seasoned climbers who wouldn't be phased, but my strategy was to never look down. Below, my partner is taking initial steps on the ledge. It's just wide enough for his boot.

In 2012, there was a pinch point where we did a step over thin air. The move was on the level and we hugged the wall. In 2024, material had exfoliated and there wasn't much to hang on to. Test all holds and watch out for ball bearing scree. (THW, photo)

Once past the pinch, there is a decent sidewalk wrapping around to the access chute. The ledge was slightly easier to traverse on our way down the mountain. (THW, photo)

I call the third challenge Bubble Wrap Chute. The rocks pop right off the mountain! In 2012, I got into a thick stash of small, slippery scree and started spinning out. I couldn't regain traction and my partner had to give me an assist. This time, we put my son in charge of plotting the course up the 80-foot chute. He zigzagged, staying on clean surface rock. (THW, photo)

I leaned into the mountain, trusted it would hold me, and had fun.

From the top of the chute the summit is a pleasant stroll away. (THW, photo)

Crest the generous Grant summit in 4.5 miles. The sweeping, full-circle panorama is spell-binding. The peak register placed by the Colorado Mountain Club had disappeared. It's becoming increasingly rare to find summit registers. I mourn the loss of the mountaineering tradition recording history, drawings, and sweet notes from kindred spirits.

(THW, photo)

I can't do justice to this terrific vantage point but I've included a few photos to give you an idea of where Grant sits in the greater landscape (and why we see it from seemingly everywhere). Looking westward, Yellow Mountain (mid-range in this photo) is an outstanding hike launched from the Waterfall Creek basin. Asserting their mighty selves are Mount Wilson, Gladstone Peak, and Wilson Peak. Little Cone is behind the fourteeners on the right. And finally, the summit of V3 just comes into the frame on the right.

To the south, Ice Lake is hidden by the southeast ridge of V4. I have several friends who have climbed V4 from the Ice Lake Basin and returned ashen faced having suffered from frequent rock avalanches. Fuller Lake is in the high basin below Fuller Peak. Golden Horn is hard to distinguish from Vermilion Peak (in this photo). Of that group, only Pilot Knob presents a technical challenge for the climber. With all those creative names in the region, I'm not sure why the bastion we were standing on was named for the 18th president of the United States. As commanding general, Grant led the Union Army to victory in the American Civil War in 1865.

To the north, Swamp Canyon flushes into the Howard Fork above Ophir. The colorful variegated divide has several summits, including Silver Mountain, San Joaquin Ridge Summit, and Oscar's Peak at the top of Blixt Road.

(THW, photo)

And finally, in the immediate east is V2. The grey summit on its left is V5. You know it's a clear day when you can see the Rio Grande Pyramid on the other side of the Grenadier Range and Needle Mountains (image-center).

And finally, in the immediate east is V2. The grey summit on its left is V5. You know it's a clear day when you can see the Rio Grande Pyramid on the other side of the Grenadier Range and Needle Mountains (image-center).

I promised a short discussion about descending on the east ridge of Grant, the shortcut route to Swamp Pass. I was on V2 a few weeks prior to this hike and watched in amazement as two climbers buzzed up the southwest ridge in less than 15 minutes. Then I watched their laborious, measured descent on the east ridge and it gave me the shivers. I got home and read some trip reports. One person turned back after an unsuccessful downclimb into the first deep notch, shown below. (South Lookout Peak is the dark gray technical summit on the left.)

In this telephoto image, the swift climbers are standing on the Grant summit before beginning their

east ridge descent. (THW, photo)

The west ridge of V2 affords a comprehensive view of the east ridge. Class 3? Class 5? Opinions are all over the board so do your research before embarking. (THW, photo)

I have many friends who have climbed Grant and every one of them has been fooled by a classic "loose end" on their way down the southwest ridge. At about 13,560 feet (below the crux wall), we followed a pounded trail just a few feet east of our upcoming route. The trail stranded us at the top of a cliffed out gully with no escape. We quickly realized our mistake (it didn't look familiar), climbed out, and recovered the proper route.

Put off by the crowds, we hadn't been to Ice Lake in several years. Deep into autumn, the trails were quiet so we decided to divert on the path linking the two lakes. The loop adds just 0.8 mile with minimal elevation gain.

(THW, photo)

Abstract painter Vasily Kandinsky wrote, "The deeper the blue, the more it summons man into infinity, arousing his yearning for purity and ultimately transcendence. Blue is the typical celestial color. Blue very profoundly develops the element of calm."

We sat lazily by the shore of Ice Lake for a good long time, attempting to process the seemingly impossible color, and delighting in the completion of a climb that tipped, "...the ordinary plane of existence on end." (THW, photo)

No comments:

Post a Comment